The North Sea Center is known for fisheries for a number of reasons – not primarily for the social science research at IFM, but among the public for a large aquarium focusing on North Sea species, among scientists for the large branch of the Danish Institute for Fisheries Research, and among the fishing industry for the flume tank – one of few such facilities worldwide where you can test a scale model of fishing gear and see how it actually functions underwater.

Most fishermen, mind you, spend a lifetime intimately getting to know their gear and its performance in different conditions…but they can’t actually see what is going on underwater once they release the net, how it interacts with the fish or whether it works they way they imagine in their heads.

So the chance to test a net in a tank of moving water that provides a giant window into the net’s performance in action is a useful tool for netmakers and fishermen alike.

I first got to see the flume tank in October, when the tank was open for the public in celebration of its 25-year anniversary. Although the tank has come to be well-known worldwide, it’s a pretty expensive facility and as such generally only used for research projects or development of large (and thus expensive) nets for large boats*, and thus many local fishermen in Hirtshals, including the former fisherman I’d met just the week before at the folkedans, had lived walking distance from the tank for years and never actually seen it. The net demonstrated for this open-house was an experimental bottom trawl with square bottom panels as an alternative to the rockhopper gear generally used along the bottom of the net. The idea of the change is that though the rockhopper does indeed “hop” over rocks, it hops fairly considerably, which lets out a lot of the fish – plus, this traditional trawl gear has generally been considered as to cause potential damage to the seabed. The alternative square panels, however, flip up individually, so that they let out fewer fish and are thought to be less damaging to the seabed.

Standard rockhopper gear (this photo from the Bjarni Saemundsson, a flashback to my time in Iceland):

The experimental net with alternative bottom gear:

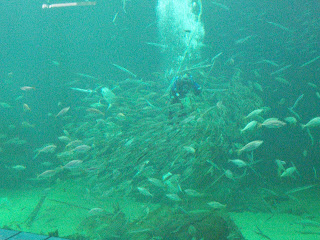

Along with the demonstration of the net in the tank, they also played video footage taken from a test of the net on a pair trawler (convenient for comparing experimental and control nets since the two are towed side by side by the same ship) in the Barents Sea. They mounted a video camera on the headrope (top) of the net looking back and it was really very cool to see how the fish behaved once they got caught (herded, really) in the net, and you could see that more escaped from the standard rockhopper net.

I’ve long thought that gear technology provides some of the best solutions to fisheries problems – rather than requiring limiting regulations to avoid bycatch of unwanted species or catch of juveniles or damage to the environment, many of the problems can be minimized by modifying the actual gear used for fishing. In any case, I was excited enough by this demonstration and by the potential of this flume tank to combine fishermen’s needs and policy/science-driven experimentation that I was determined to see some more of how this tank was used in practice. Which I had the chance to do on two different occasions – one an experimental use of the tank to modify an existing net and the other a workshop for fishermen to see their nets in action.

In mid-November, I came back to the tank to watch a test of an experimental net used for sampling salmon fry. Since one of the main complaints made by fishermen against scientific surveys is that the scientists do not test or update their fishing gear to successfully catch fish (scientists, on the other hand, will tell you that the purpose of surveys is not to catch fish but to sample the same locations using the same methods from year to year to have a frame of reference for comparison of stock sizes from year to year; I think both points have merit and have been largely discounted from by the other party – maybe more on this another time), it was interesting if just for the fact that it was a test of a scientific survey net.

Here’s the net in the tank:

The view of the net from the top of the tank – it basically looks like a large swimming pool…except you’d better watch out before you dive in and get caught like an unlucky fish.

Even more interesting than the net itself, though, was getting to see how nets are measured while in the flume tank – how this state-of-the-art gear research actually works. Although the system is highly sophisticated, the methods used to measure the important parameters of how the net works (mostly focused on the dimensions of the net at different points while towing – here mimicked by water circulation – at different speeds) are fairly simple, based on moving cameras with sensitive position coordinates until they point to the exact points to be measured and then determining the distance between the cameras. Elegantly simple.

Here are two of the guys who work at the flume tank, experts at taking all these measurements:

Based on the initial results, the team working at the flume tank can also make slight alterations to the design of the net – how it is rigged, the choice of doors used to keep the net open, etc. and then re-try the net to see the effect of these changes.

Here they are making some adjustments to one side of the net (look at the tiny door! This is what you get with 1:10 scale model…it’s almost cute.)

Most netmakers, unlike those working for scientific research vessels, have another purpose in mind beyond designing the best nets: convincing fishermen to buy them. And so another important function of the flume tank is that it allows fishermen who use these nets come and see how they look underwater. This is useful because it provides fishermen with up-to-date information on the available gear technology and helps them understand how they can get the best performance out of their own gear, but also because it helps gear companies sell their products. And so I had the opportunity to spend three days attending a flume tank workshop held by Hampiðjan, an Icelandic netmaking company and one of the leading gear technology companies in the world, with net lofts all over – Lithuania, Russia, New Zealand, Namibia, Denmark, Ireland, Norway, the Faeroe Islands, Newfoundland, and the USA.

The workshop participants were similarly from all over the world – from South Africa to Alaska, Iceland to Argentina, and mostly captains aboard large fishing vessels, which meant that they were the people who saw these nets in action more often than anyone else and also the people most interested in staying at the cutting edge of fishing technology. For three days, they watched net after net demonstrated in the flume tank and attended seminars on new fishing technology, both nets and other products shown and sold by other companies at the workshop, including strong but lightweight ropes and remote sensing technology used to determine how the trawl is working while in the water.

The skippers all seemed interested in learning as much as they could about this new technology, particularly things they might be able to try on their own boats – everyone wants to have the best gear out there.

Even fishermen from Iceland, where the ability to catch is strictly based on quotas and the decision of how much to catch is theoretically decided based on market prices, quality of the fish available, processing capacity, etc. (at least according to the office-based employees I talked to from the large companies), were set on talking about which fishermen were best based on who was able to catch the most, and any gear that could help gain that edge to catch more fish was thus extremely desirable. The development director for Hampiðjan explained to me that different people within industry focus on different objectives: the skipper wants to catch the most, the engineer wants to use less fuel, and the fleet manager wants to make the most money. By providing new technology, of course, companies like Hampiðjan try to make it easier to accomplish all these goals.

Inherent in this is also an ingrained desire for progress, to remain at the forefront of the industry. Although many of the new nets shown throughout the workshop and many of nets and other types of gear advertised seemed to provide important improvements over previous fishing methods, there also seemed to be a trend towards trying new products just for the sake of progress itself. As a South African skipper explained to me, “as soon as you think you’re on top of the game, you’re starting to lose it…that’s fishing.” Experimenting with new gear had worked well for him: he described fuel savings and higher quality catch with a new net he had switched to, but he also openly admitted that he hadn’t focused on these specific factors when deciding on the new net but mostly just wanted to keep improving and not keep using the same gear. A Faeroese netmaker explained the desire for new technology by saying that fishermen are much like schoolchildren with a new toy – once you convince one to try a new net, they all want it. This is also a tendency he had learned how to capitalize on: he says he always makes sure to test a new net with the most successful fisherman with the best boat, and then when he catches the most fish (as always), other fishermen will say it was because of the net and want to try it themselves. Unlike the fishermen, who seemed very focused on the ability to catch fish, this netmaker said the main limiting factor was actually the ability to process fish onboard the boat – those with a greater processing capacity, he said, are thought to be better fishermen when really they just have better boats.

I kept wondering, though, whether all this new technology was really as necessary as it was made out to be by the companies trying to sell their gear. I understand the point made by the president of Scanmar, the company selling remote sensing devices to measure the trawl’s performance while in use, that “there’s so much money hanging back there” that these boat’s cannot afford to not be successful on their fishing trips – and thus, he says, cannot afford to not use his technology. What wasn’t entirely clear from the workshop, however, was why large, expensive boats with fancy, expensive gear are better than smaller lower-tech boats. If everyone agrees that there’s a finite amount of fish that can be caught by each boat – we can quibble later over how much and who gets to decide how much goes to each boat, but in most places today determined by how much quota share you have purchased, not your ability to catch the most fish – do you really need the newest, fanciest equipment? In a lot of cases, new technology seems to be helping to maximize the amount of profit from fishing: reducing fuel costs, increasing selectivity and reducing damage while in the net to improve quality, replacing the high number of fishermen on numerous small vessels with fewer, better-paid fishermen on fewer, larger vessels. I’m still not sure whether profit maximization in and of itself is a desirable goal – it’s the point where pure economics begins to mix with cultural and social values, always a messy process.

Even without answering this question, though, developments in gear technology still hold significant promise since they provide consumers with higher quality fish and use less fuel, both important goals in their own right in addition to allowing fishermen to catch less without losing money, and also can be more selective about the fish caught (reducing bycatch of both unwanted species and of juveniles) and can reduce unwanted negative environmental impacts. Although at this workshop, everything was presented as a way of improving profit (reduce fuel expenses, increase quality and thus selling price of catch, reduce unwanted bycatch in order to more carefully select which quotas to use and to avoid breaking regulations), it also provides an opportunity to “slip in” modifications to gear and fishing technique that help with sustainability.

Fuel savings was one of the main themes of this workshop due to the high fuel prices that today make up a considerable percentage of the cost for a fishing trip. (See my earlier musings on worries about fuel use in fisheries here).

Most of the fuel-saving techniques presented were variations on the theme of reducing the trawl’s resistance while being pulled through the water, a very energy-intensive operation. Ways to do this ranged from using stronger but lighter-weight ropes and netting to new designs of nets and trawl doors that produce less resistance in the water to adjustments in the rigging and alignment of different components of the net to get the maximum fishing capacity out of each haul.

Size- and species- selectivity has also become increasingly important to fishermen as they have to adjust to regulations that restrict both what and how much they are allowed to catch. This net was developed by an Irish netmaker for pelagic boats in the Shetland Islands. With reduced quotas, the fishermen wanted to make sure they were only catching the largest – and highest-priced – fish, and so they designed a net with separator panels to allow small fish to escape. (In this model, I’m a particular fan of the illustrations of the escaping fish.)

I should mention here that the president of Scanmar was particularly adamant that this type of size selection is a bad idea for pelagic species, since he says that 80% of fish that escape through meshes in nets do not survive. I know that some pelagic species (particularly herring) are easily damaged by being touched, unlike hardier groundfish, but can’t tell you for sure what the “truth” might be. (This is a common theme I’m finding in fisheries – it’s not just that people disagree about interpretations or priorities about what to do with fish, but also about basic facts. My natural inclination is to say we need more science, but here even science is seen as just one of many viewpoint.)

For me, though, the most interesting of the nets were the ones designed to avoid cod. Whatever you might think about the reductions in cod quotas or the actual amount of cod in the sea, the fishermen have been facing the tricky task of trying to catch other groundfish – mostly haddock, redfish, and flatfish – without catching cod. This has been tried before – while at Williams-Mystic, I heard about the development of the Eliminator Trawl at Rhode Island Sea Grant, a net that is designed with particularly large meshes in the bottom of the net so that cod, which swim downwards once in the net, can escape, while haddock, which swim upwards, remain in the net. With the New England haddock fishery consistently being closed before the quota has been reached due to excessive cod bycatch, the idea of the Eliminator was to allow fishermen to catch more of the haddock they were trying to target while avoiding the cod. I also heard that the same principle was tried in Scotland and Ireland 25 years ago, but for some reason never caught on.

With the reduction in the cod quota in Iceland, where discards are illegal (unlike in the EU, where discards are mandatory and thus fishermen have been required to throw back large quantities of cod), it is imperative that fishermen be able to target groundfish species for which they have quota without catching too much cod. Knowing that this will be an important need for the next few years, and not just in Iceland but throughout the North Atlantic, Hampiðjan has developed new bottom trawls that allow cod to escape.

This giant net, brand new (has never been used, and brought out for sale for the first time at the workshop), is designed to catch redfish and haddock but not cod, specifically in response to the cod quota reduction in Iceland.

This net uses a separator panel between the top and bottom of the net to sort between cod and haddock, which collect in two separate cod ends. This is convenient because it allows the fisherman to decide just how selective to be: if he doesn’t want any cod, he can leave the cod end open, but if he wants to just catch the very largest cod while being less selective about haddock, he can also use two different cod ends to keep all the haddock but let more of the cod escape.

Although unfortunately fisheries management has many problems that can’t be solved by designing new gear technology, I must say that this is one of my favorite ways to deal with problems in fishing. Rather than making rules and setting up restrictions, you provide a tool to help the fishermen catch only what they want and reduce the unwanted side effects. Though I may not be an unqualified advocate of progress for its own sake, this is a prime example of the power of progress.

*Most nets tested in this tank are built and tested at a 1:10 scale, and even a few of the nets demonstrated for Hampiðjan just barely fit or couldn’t be rigged quite as they would in real-life due to size constraints. Jesper, a former fisherman and now an economist studying fisheries at IFM, reckons that the small trawl net he used to fish with (fairly normal for small-boat fishing) is the only net that’s been tested in the flume tank at full size. Since most fishermen don’t happen to have become social scientists and become friends with other researchers at the North Sea Center, they generally don’t have the opportunity to try this.

And Mom and Jason warming themselves in the evening at Tivoli Gardens.

And Mom and Jason warming themselves in the evening at Tivoli Gardens. But after they left this morning, I had New Year's Eve on my own to celebrate with the Danes.

But after they left this morning, I had New Year's Eve on my own to celebrate with the Danes. To my American sensibilities, this seems like a horribly bad idea. There were fireworks shooting off in all directions, across the ground and towards buildings and young children throwing sparklers along the sidewalks. The favorite, however, seemed to be explosives without the firework that would boom so loudly that they left my ears ringing and literally shook the sidewalk. These were thrown right in the road, where buses, taxis, and later police and ambulance vans drove right past, seemingly unphased by the explosions.

To my American sensibilities, this seems like a horribly bad idea. There were fireworks shooting off in all directions, across the ground and towards buildings and young children throwing sparklers along the sidewalks. The favorite, however, seemed to be explosives without the firework that would boom so loudly that they left my ears ringing and literally shook the sidewalk. These were thrown right in the road, where buses, taxis, and later police and ambulance vans drove right past, seemingly unphased by the explosions.